Introduction

Evolve is a high-performance benchmark designed to measure the capabilities of modern graphics hardware across desktop and mobile devices.

On most graphics cards, this measurement is straightforward: for each draw call (a request to render geometry on screen) Evolve is able to time this operation precisely.

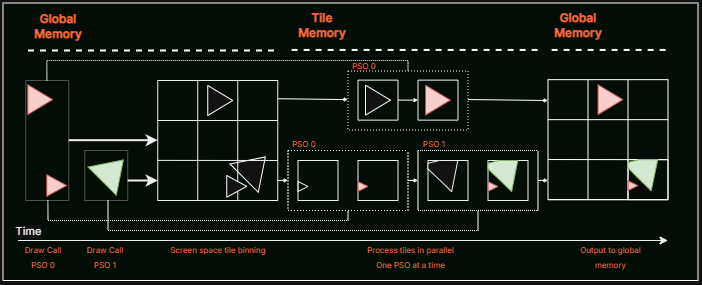

Most mobile chips, however, operate fundamentally differently. To maximize battery life and minimize heat generation, mobile GPUs don't render the entire screen at once. Instead, they divide the screen into small rectangular sections called "tiles" and process each tile using fast tile memory. This tiling architecture is exceptionally power-efficient, but it fundamentally changes how rendering work is organized.

When Evolve requested timing information on a tiling GPU, it didn't receive accurate data. The timestamps only captured a small fraction of the actual work, causing some devices to report artificially inflated scores, up to 10 times higher than their true performance.

Our solution is to measure the entire rendering phase as one cohesive unit of work, the complete render pass. By measuring the render pass in aggregate all GPU architectures are handled consistently and can report reliably. Unfortunately, as a result, our rasterization scores on mobile will decrease by approximately 10x to reflect actual performance, while desktop scores will see a minor 2-4% reduction due to more comprehensive measurement. Thankfully this correction ensures Evolve provides accurate, comparable performance metrics across all device types.The following sections dive into the technical details of this issue and our solution for those interested in the underlying graphics architecture and implementation specifics.

Geometry culling

At the heart of the rendering pipeline in Evolve, and one of the reasons for its great performance, is an algorithm that’s responsible for removing hidden objects from being submitted to the rasterization pipeline. In Evolve we’ve chosen an algorithm called two-pass occlusion culling that we have running all the way at the beginning of a particular frame.

This algorithm runs on the GPU, counts up all objects that ultimately need to be rendered, and will then emit what’s known as indirect draw calls that end up actually doing the rendering.

This is an algorithm that we had implemented relatively late into the project and something that deviated from our old way of doing things in which we were culling and recording individual draw calls on the CPU.

Due to the way this algorithm works and how we structured the internals of the rendering pipeline in Evolve, this had resulted in the following order of operations. (Note that these operations in practice happened relatively far apart from each other).

begin render pass

for each bucket:

record timestamp

indirect draw

record timestamp

end render pass

In the next section, we'll explore how tiling GPU architectures work, which will reveal why our original approach of recording timestamps around individual indirect draw calls was problematic.

Understanding Tiling GPU Architecture

Tiling architectures exist primarily to save power. Memory access to DRAM is one of the biggest power drains in graphics processing. These accesses eat up bandwidth, draw substantial power, and create heat under load. By keeping data in fast “tile” memory and minimizing trips to system memory, tiling GPUs deliver solid performance while preserving battery life.

When rendering a frame, a tiling GPU works through all tiles, processing drawing operations for each tile while keeping intermediate results in fast tile memory. This cuts down system memory accesses dramatically compared to rendering the entire screen at once.

This tiling process happens in two distinct phases: binning and rendering. During binning, the GPU analyzes all geometry in the scene and determines which tiles each piece of geometry touches. In the rendering phase, the GPU processes each tile individually, executing only the drawing commands relevant to that tile while keeping all intermediate data in tile memory. Only when a tile is complete does the GPU (in most cases) write the final result back to system memory.

Note that tiling implementations vary by vendor, and the explanation and image above provide only a high-level overview. For detailed information on specific vendor implementations, please refer to the resources listed in the references section at the end of this post.

The measurement problem

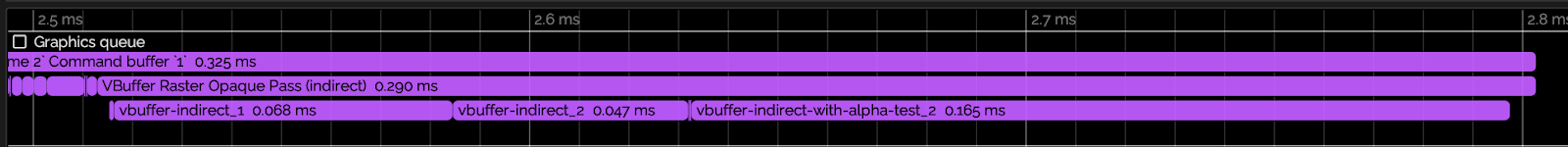

Previously, Evolve profiled the time each individual indirect draw command took by querying timestamps before and after every command in the graphics command buffer. After the command buffer completed, we calculated the differences between timestamps to determine each indirect draw's duration. This approach works correctly on immediate mode GPUs, where draw commands are retired in submission order.

Above image shows the render pass VBuffer Raster Opaque Pass (indirect) with correct timing markers for each indirect draw command (vbuffer-indirect_*) on an immediate mode GPU.

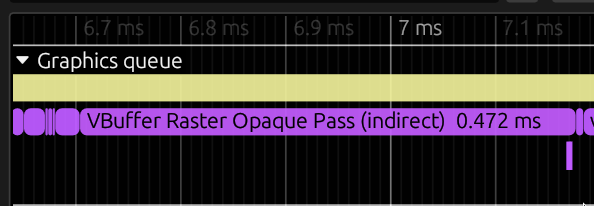

However, on tiling GPUs, the execution model is fundamentally different. Indirect draws are processed on a per-tile basis, requiring each draw command to be executed across every tile. Accurately measuring a single indirect draw's duration would require capturing both the up-front binning work, plus the cumulative rendering work across all tiles for just that draw. Graphics APIs don't expose this level of granularity, nor would it be efficient to query and store timestamps for every tile-draw combination. As a result, on some tiling GPUs, those timestamps are recorded/sampled at the end resulting in infinitely small differences between them, as can be seen in the next screenshot:

Our solution

We've restructured our timing measurements to query timestamps at the render pass boundaries rather than around individual indirect draw commands. At these boundaries, the command buffer is not split and executed multiple times as it is with tiling architectures, providing a consistent measurement point across all GPU architectures.

begin render pass

for each bucket:

record timestamp

indirect draw

record timestamp

end render pass

Before

record timestamp

begin render pass

for each bucket:

indirect draw

end render pass

record timestamp

After (our solution)

Conceptually, this is what Evolve was already calculating for its rasterization score by summing up all individual indirect draw durations, but now we capture it directly as a single duration over the entire render pass.

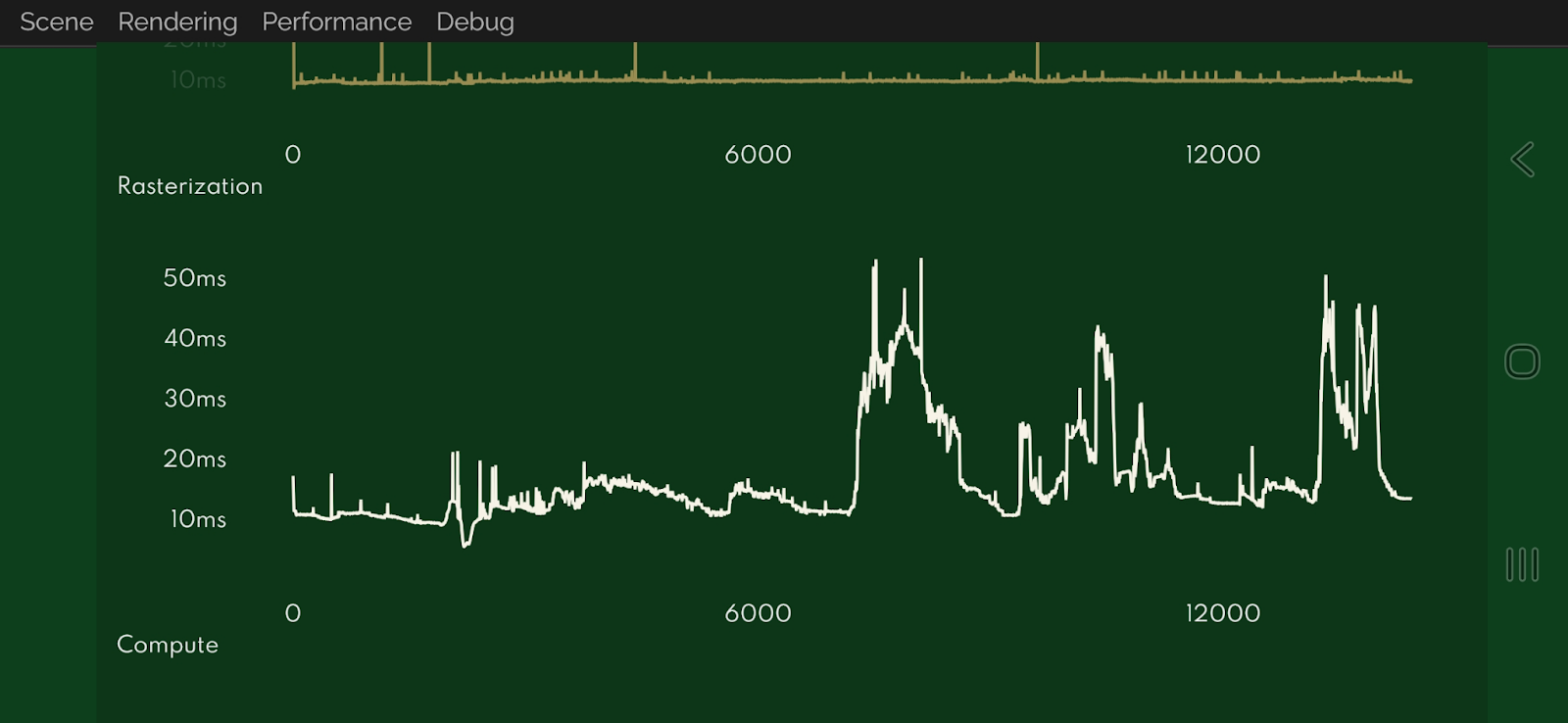

On above we have the old, incorrect, rasterization timings for tiling GPUs. On below are the correct timings after applying our solution.

Results on Immediate Mode GPUs

On immediate mode GPUs, we confirmed that the total render pass duration is only marginally longer than the sum of all individual indirect draws within it. The slight increase in duration (and corresponding decrease in scores) is expected: we now account for render target loading (when not cleared) and storing (writing the final result to memory), operations that were previously unmeasured.

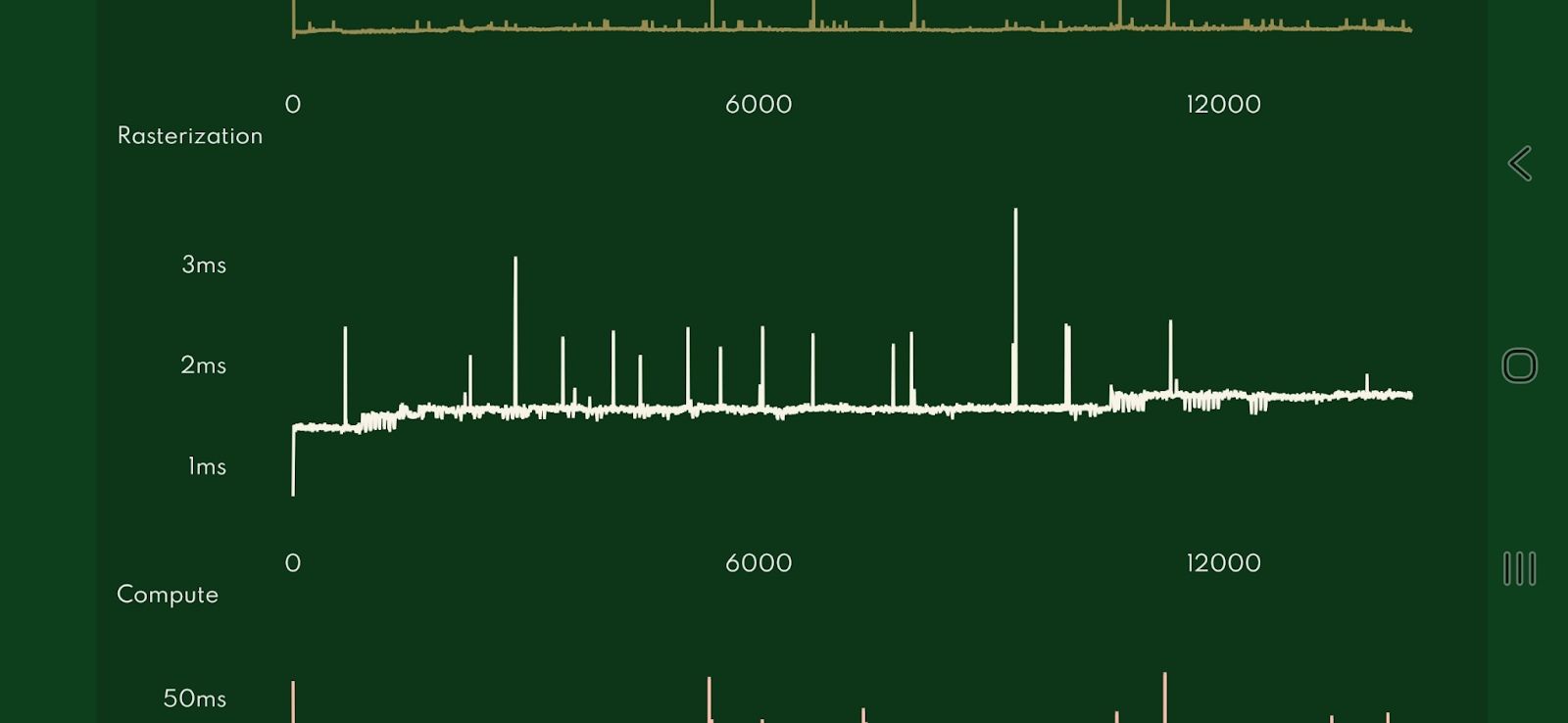

Results on Tiling GPUs

On tiling GPUs, our detailed rasterization timing graphs have been transformed. Instead of the flat line indicating near-zero individual indirect draw times, they now follow the same curvature seen on immediate mode GPUs, demonstrating that we're accurately capturing the workload duration.

References

- Vulkan QCOM Tile Shading Extension

- Qualcomm Adreno GPU Documentation

- ARM GPU Best Practices

- Samsung Galaxy GameDev: GPU Framebuffer

- Tile-Based Rendering GPU - WP557

- https://interactive.arm.com/story/the-arm-manga-guide-to-the-mali-gpu/

.jpg)

.avif)